Translate this page into:

Retrospective Review Analysis of Interventional Radiologic Endovascular Coil Embolization versus Neurosurgical Clipping in Management of Intracranial Aneurysms

Address for correspondence Abhinav Amarnath Mohan, MBBS, DNB Radio Diagnosis, DMRE, FVIR, Department of TIFAC-CORE Interventional Radiology, Acharya Vinoba Bhave Rural Hospital (AVBRH) & Shalinitai Meghe Super Specialty Centre, DMIMS Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College (JNMC), Sawangi Meghe, Wardha 442005, Maharashtra, India (e-mail: dnbabhinavmohan@gmail.com).

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background

Ruptured intracranial aneurysm and nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are synonyms and indicators of a high-risk medical emergency. They can be treated either with endovascular approach with interventional radiological (IR) coil embolization or by neuro-surgical (NS) approach by clipping with each having their own merits and demerits and time-tested applications either requiring perioperative expectant management to prevent or curb complications of SAH or post-procedure aiming to achieve better patient outcomes. We conducted this retrospective study to analyze and gain experience from our past cases managed at tertiary care super specialty center and serve as baseline study to implement further studies and have insight for future trends in rural hospital setup in management of critical cases aimed to improve and upscale clinical outcomes in these patients.

Materials and Methods

Study comprised patients belonging to either of two groups, depending on the management they underwent. Analysis was done by using descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results

The overall study population consisted of 29.83% males and 70.18% females in this study. The overall mean age was found to be 47.33 years (standard deviation [SD] 15.68 years). In IR group, the pre- and post-procedure modified Fisher's scale (MFS) values were 53 and 50, respectively, in 31 cases, whereas the same in NS group were 43 and 53, respectively, in 23 cases. The difference change in MFS for pre- to post-procedure in IR group was small (3) and showed decreasing trend (from 53 to 50 as well as in individual Fisher grade) whereas that in NS group was big (10) and showed increasing trends (from 43 to 53 as well as in the individual Fisher grade).

Conclusion

Endovascular coil embolization is the surgery of choice for management of intracranial aneurysm and is minimally invasive procedure with favorable comparative outcomes on MFS than NS clipping group in our study. We recommend undertaking further prospective comparative study, incorporating our study principles and observations with inclusion of prospective clinical scale–modified Rankin's scale (MRS).

Keywords

intracranial aneurysm

interventional radiologic endovascular coil embolization

neurosurgical clipping

Introduction

Globally, nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) due to ruptured intracranial aneurysm is the most important cause of morbidity and mortality with high-risk outcomes. Ruptured intracranial aneurysm due to nontraumatic SAH presents with clinical symptom of “worst headache of life” and is routinely diagnosed in emergency radiology call on plain computed tomography (CT) scan.1 Other clinical presentations vary from nausea, vomiting, loss of consciousness, transient motor deficits, convulsion, or seizure, in association with severe headache as prominent feature with neck pain, meningismus, and/or hyperirritability. If clinically suspicious and equivocal on CT scan, lumbar puncture reveals cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) xanthochromia suggestive of SAH.2,3

Routinely post CT suggestive of SAH, with high suspicion for aneurysmal bleed, contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) cerebral angiogram are performed to search and demonstrate aneurysm. If aneurysm is not demonstrated on CECT angiogram, catheter digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is done as gold standard to rule out the aneurysm. Mostly on catheter DSA, the location, size, site, number, configuration and, if contemplated for endovascular management, the study of relevant vascular anatomy and working angle is done for planning of intervention. If DSA is negative for aneurysm, repeat DSA is advised on follow-up at 7th or 15th day to demonstrate aneurysm if it at all was not demonstrated on previous DSA due to spasm. Depending on the risk evaluation and protocol, either endovascular or neurosurgical (NS) management is contemplated.4,5 Thereafter clinical evaluations are made with SAH grading scales6 and routine investigations under general anesthesia, and the case is planned for interventional radiologic (IR) endovascular coil embolization or NS aneurysm clipping. Hypertension control and peri- and postprocedural management have undergone significant changes and neuro-intensive care unit (ICU) protocol formulations as per recent guidelines and research like the advances in aneurysm management and technology. The recent advances in coil embolization techniques, hardware, and availability of advanced catheter laboratories and biplane as well as instrumentation in NS clipping and advanced neuronavigation software have revolutionized the aneurysm management and outcomes.7 Among the two principle streams in management of aneurysm, endovascular approach has been highlighted and has been in limelight than NS approach; however, future studies and interdepartmental studies and registries could shed more light on this controversial aspect in management of aneurysm.6,8,9 Although sometimes postendovascular management NS backup is required, sometimes it may be necessary to manage the case with hybrid approach, interdisciplinary help or multidisciplinary approach to manage or prevent complications such as vasospasm and its sequelae, intra- or postprocedure hemorrhagic complications and its sequelae as seen on intra- or postprocedure DSA/CT scan/MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), endothelial dysfunction, cerebral edema, hydrocephalus, ischemia, and implementation of various measures for aiding neuroprotection.9–11 These two commonly used management approaches for aneurysm treatment have their individual merits and demerits.6,9,12-16 We conducted this retrospective study to analyze and gain experience from our past cases managed at tertiary care super specialty center and serve as baseline pilot study to implement further studies and have insight for future trends in rural hospital setup in management of ruptured intracranial aneurysms aimed to improve and upscale clinical outcomes in these patients.17–21

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective observational study conducted in the interventional radiology department of a tertiary care medical college and super specialty hospital situated in a rural area. The patients who presented with either diagnosis of ruptured intracranial aneurysm or nontraumatic SAH who were either later diagnosed on CECT cerebral angiography or on DSA with baseline plain CT suggestive of ruptured intracranial aneurysm (either of anterior or posterior circulation) and underwent management with endovascular coil embolization by IR or NS aneurysm clipping in respective departments of this hospital were included in this study during 2014 to 2018 on the basis of a predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Study comprised patients belonging to either of two groups depending on the management they underwent (endovascular coil embolization or NS clipping). Analysis was done for demographic data as well as those pertaining to findings on pre- and/or intra-postprocedure plain CT scans and CECT and/or DSA (as per availability on hospital PACS). Statistical analysis was done by using descriptive and inferential statistics and online calculator Social Science Statistics. Software used in the analysis included SPSS 22.0 and Graph Pad Prism 6.0. For statistical purposes, p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Management of Ruptured Intracranial Aneurysms

We reviewed analysis of endovascular coil embolization treatment of intracranial aneurysms and compared results with those of open NS clipping. Between January 2014 and October 2018, total 57 patients were treated for intracranial aneurysms either endovascularly (32 patients) or neurosurgically (25 patients).

Endovascular Coil Embolization (Interventional Radiology Group)

In this group through transarterial access and routinely right common femoral artery access, endovascular coil embolization is performed using special detachable platinum micro coils: three-dimensional (3D) coils framing and filling hyper soft coils. Depending on anatomy and pathology in special cases, stent-assisted coiling and/or balloon remodeling – assisted coiling are performed under roadmap guidance in catheter laboratory by interventional radiologist using appropriate coaxial guiding catheters with compatible micro-wires and micro-catheters.

Aneurysm Clipping (Neurosurgery Group)

In this group, clipping by craniotomy approach is done by the neurosurgeon at neck of aneurysm. Preprocedure planning is done on 3D reconstructions on CECT cerebral angiogram or conventional 3D rotational DSA with or without neuronavigation software for guidance and planning surgical pathway.

Inclusion Criteria

Diagnosed case of ruptured intracranial aneurysm/non-traumatic SAH undergoing either IR or NS management.

Exclusion Criteria

Not undergoing either IR/NS management

Other causes of nontraumatic SAH

Traumatic SAH

Nonavailability of radiologic images on PACS

Cases with incomplete postprocedure radiologic images excluded from complication results

Patients not giving informed consent to undergo procedure/radiologic study

Results

This study comprised 57 patients in whom demographic data were studied, out of whom 32 underwent IR coiling and 25 underwent NS clipping. For our review analysis, we studied 23 aneurysm clipping cases and 31 aneurysm coiling cases owing to nonavailability of the remaining cases on PACS. Retrospective analysis of cases was done and included in our results based on findings on available pre-/postoperative CT/MRI and/or pre-/post- and intraoperative DSA. Comparative analysis was done in the two groups: NS clipping group and IR endovascular coiling group.

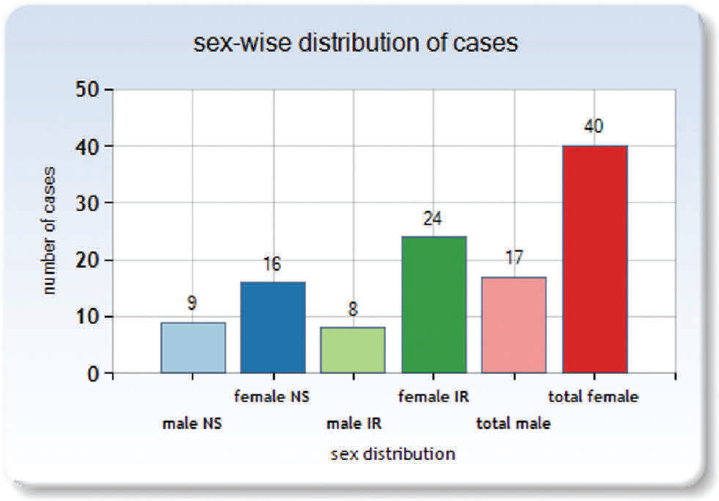

The gender distribution of the studied patients showed that IR endovascular coiling group had 8 males and 24 females whereas NS clipping group had 9 males and 16 females. The overall study population consisted of 29.83% males and 70.18% females in this study. The analysis of age groups of the patients showed that in IR group the most commonly affected age group was 47 to 56 years (25%; 8 cases), followed by 57 to 66 years (21.88%; 7 cases) and 5 cases (15.63%) each in 27 to 36 and 37 to 46 years. The youngest patient belonging to IR group was a 10-year-old girl. In NS group, the most commonly affected age group was 47 to 56 years (28%; 7 cases), followed by 57 to 66 years (24%; 6 cases) and 37 to 46 years (20%; 5 cases). The most common age groups affected were as similar to those in IR group. The youngest case in NS group was a 10-year-old boy. The mean age of patients in IR group was found to be 46.88 years ± standard deviation (SD) 16.59 years, whereas in NS group it was found to be 47.92 years ± SD 15.08 years. The overall mean age was found to be 47.33 years (SD 15.68 years). The age groups were comparable, and there was no statically significant difference in the age groups of patients (►Table 1).

| Mean age | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| IR group | 46.88 | 16.59 |

| NS group | 47.92 | 15.08 |

Abbreviations: IR, interventional radiological; NS, neurosurgical; SD, standard deviation.

In IR group, the pre- and postprocedure modified Fisher's scale (MFS) value was 53 and 50, respectively, in 31 cases, whereas the same in NS group were 43 and 53, respectively, in 23 cases.

The difference change in MFS for pre- to post-procedure in IR group was small (3) and showed decreasing trend (from 53 to 50 as well as in individual Fisher grade), whereas that in NS group, it was big (10) and showed increasing trends (from 43 to 53 as well as in the individual Fisher grade), thus implying betterment in MFS in IR group and worsening in NS group.

The NS group revealed total of 23 aneurysms clipped, out of which Acom aneurysm cases were highest frequency followed by middle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysm in anterior circulation (location wise). The Acom aneurysms and female sex of cases were in frequent association in this group.

The IR group revealed total of 31 aneurysms coiled, out of which MCA aneurysms were in highest frequency, followed by both Acom and internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysms subgroup in anterior circulation (location wise). The association of both Acom and MCA aneurysm cases had dominance of female sex in this group.

In posterior circulation aneurysms in both groups were less in number and had no dominant location although Pcom-PCA aneurysm location had high frequency in combined study population (►Fig. 1; ►Table 2).

- Gender distribution of the studied cases.

| Group | Acom | MCA | ICA | Pcom | PCA | Vertebral | Basilar | VB | Cases total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS clipping | 8 | 7 (L4, R3) | 3 (RS2C1) | 4 (R2, L2) | 1 (L) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| Endovascular coiling | 6 | 8 (R5, L3) | 6 (RS3,B1,C1, LS1) | 3 | 1 Pcom-PCA | 4 (R1, R2PICA, L1PICA) | 2 | L1 | 31 |

Abbreviations: ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; NS, neurosurgical; Pcom, posterior communicating artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; PICA, posterior inferior cerebellar artery; VB, vertebrobasilar.

S = supraclinoid ICA, B = ICA bifurcation, C = cavernous ICA, L = left, R = right.

The comparative analysis for postoperative complication in terms of major stroke/infarction on postprocedure imaging reveals similar number of events with slight difference in presentation territories in both the groups. There were six anterior cerebral artery (ACA) territory infarctions, four MCA territory infarctions, and two PCA territory infarctions in postendovascular coiling cases, whereas five MCA territory infarctions, four ACA territory infarctions, and two PCA territory infarctions with one involving head of caudate nucleus.

The other significant complications in IR group were two intraprocedural aneurysmal ruptures (one Acom and other Pcom aneurysm, both with good outcomes) and two intraprocedural nonresponsive spasms, one nonresponsive ACA occlusion post-coiling, one IVH (intraventricular hemorrhage) case not requiring EVD (external ventricular drainage), while the other IVH case required decompressive craniotomy.

The NS group mostly on imaging revealed four IVH cases. Of them, two required EVD, one required hydrocephalus with ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt; 7 cases with craniotomy site thick SDH (subdural hematoma) with pneumocephalus and one with major brain herniation via craniotomy site owing to severe edema and mass effect.

Similar frequencies for cerebral major edema and intraparenchymal hemorrhage were noted in both the groups.

Minor complications in IR group were seen as puncture site hematoma and postoperative minor infarcts whereas in NS group thin SDH at postoperative craniotomy site with pneumocephalus and postoperative minor infarcts were noted.

There was significant difference in pre- and postoperative MFS in both the groups, showing rising trend and overall scale value and frequency difference favoring endovascular IR coil embolization than NS clipping (►Tables 3–6).

| Postoperative infarction territory | ACA | MCA | PCA | Caudate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS group | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| IR group | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

Abbreviations: ACA, anterior cerebral artery; IR, interventional radiological; MCA, middle cerebral artery; NS, neurosurgical; PCA, posterior cerebral artery.

| Imaging findings | IR endovascular coiling group | Neurosurgical clipping group | Special mentions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative spasm | 2 cases | No data available | Unresponsive spasm |

| Intraoperative unresponsive ACA occlusion | 1 case | No data available | Unresponsive occlusion |

| Major cerebral edema | 2 cases | 3 cases | Global edema |

| Minor cerebral edema | 4 cases | 2 cases | Regional |

| Craniotomy with pneumocephalus | 1 case | 3 cases | In coiling group, it was required as decompressive measure |

| Craniotomy with pneumocephalus with EVD | 0 case | 2 cases | No EVD for endovascular group secondary to IVH |

| Craniotomy with VP shunt and hydrocephalus | 0 case | 1 case | No VP shunt required in endovascular group |

| Midline shift due to mass effect | 2 cases | 2 cases | One each in both groups due to intraparenchymal hemorrhage; other due to IVH |

| Minor territorial infarcts | 6 cases | 11 cases | Focal regional/watershed/subcortical white matter/multiple tiny infarcts |

| Major bilateral territorial infarcts | 1 case | 2 cases | Bilateral major territorial infarction |

| Craniotomy with pneumocephalus with thick SDH | 1 case | 7 cases | One in clipping group was bilateral SDH |

| Intraparenchymal hemorrhage | 1 case | 2 cases | One in clipping group associated with IVH |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 2 cases | 2 cases | IVH with SAH |

Abbreviations: ACA, anterior cerebral artery; EVD, external ventricular drainage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; NS, neurosurgical; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; SDH, subdural hematoma; VP, ventriculoperitoneal.

| MFS score |

Mann-Whitney U test U value 202 Z score = −2.25265 p = 0.02444 Result significant at p < 0.05 |

||

| Preoperative | Postoperative | ||

| Endovascular group | 53 | 50 | |

| Neurosurgical group | 43 | 53 | |

Abbreviations: MFS, modified Fisher's scale.

| Groups | Preoperative cases | Postoperative cases | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFS grade | Neurosurgical group (23 cases) | Endovascular IR group (31 cases) | Neurosurgical group | Endovascular IR group |

| 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 9 |

| 1 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 8 |

| 2 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 5 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

Abbreviations: MFS, modified Fisher's scale; IR, interventional radiological.

Discussion

Nontraumatic SAH is the most common presentation of ruptured intracranial aneurysm requiring multidisciplinary management including interdisciplinary team effort to achieve better clinical outcomes and results. In the past few years, a revolution has occurred in the techniques and technology of management of intracranial aneurysm. Nowadays, endovascular approach is preferred over NS approach owing to minimally invasive and early postprocedure recovery as compared with more recovery time postcraniotomy status in postoperative uneventful cases.22

The most commonly used approaches for management of ruptured intracranial aneurysms are IR coil embolization approach or NS aneurysm neck clipping, apart from neuro-intensive care (management of hypertension and postoperative triple H therapy, management of vasospasm) and general management for better outcomes.7,8,10–13

This research was done as pilot study in rural hospital setup as review analysis to compare IR and NS groups and formulate further clinical studies.

In our study, there were more females with intracranial aneurysm, with average age of patients in our study being 47 years with overall high frequency for Acom and MCA aneurysm locations. Suarez et al1 in their study mention regarding higher risk of intracranial aneurysms to women than men. Connolly et al7 also mention in their guidelines paper about female sex as risk factor for intracranial aneurysm and adult age around 50 years as significant cause for aneurysmal SAH. Pierot et al23 also mention in their paper that Acom aneurysms were most frequently encountered location, followed by ICA and MCA aneurysms. The authors also mention that embolic events are more common in MCA aneurysm. Although clippings have more preference in general overcoiling, in higher age groups coiling was preferred over clipping. They also mention about cases of multiple aneurysms. Similarly in our study we had a dual aneurysm case with aneurysm at the left vertebral artery-PICA origin with another at right MCA bifurcation, managed by coiling both aneurysms with technical success.

Various strategies for management of ruptured aneurysm and SAH, management of intra- and postoperative complication, and preventive strategies have been discussed by Connolly et al,7 Fraser et al,8 Rabinstein et al,10 Varelas et al,11 Macdonald et al,12 Sekhar and Chanda,13 and Pierot et al23 in their papers, which we have been following. Newer guidelines are also implemented time to time in terms of management pre-, peri-, and postoperative periods for achieving better outcomes with interdepartmental cooperation, interdisciplinary management, and supportive neurointensivist and neurosurgeon and dedicated paramedical staff. We had two cases (one each of Acom and Pcom aneurysms) with intraoperative aneurysm rupture during planned coil embolization who were managed successfully intra- and postoperatively with good outcomes and were uneventful on discharge and follow-up. Both cases were nonhypertensive and required tailored dose management for nimodipine and neurointensivist care.7,8,10–13

The studies by Oliveira et al,24 Frontera et al,25 Kramer et al,26 and Dengler et al27 have highlighted and compared relevance of various SAH grading scales and its clinical significance. The prognostic utility of these scales and their individual as well as comparative significance have been vastly discussed and studied. In our study we have taken into consideration the results of MFS and its outcomes in review analysis of IR and NS groups.24–27. Similar to conclusions by Kramer et al26 and Dengler et al,27 in our study, there was significant incremental rise in the MFS in the NS versus IR groups, wherein there was absolute rise in MFS score (postoperative vs. preoperative) as well as in individual comparitive case-wise MFS grading in the NS versus IR group, which yields to conclude that endovascular coil embolization outcomes are better than NS clipping in our review analysis; higher MFS group score and grades are at increased risk for vasospasm and delayed infarction, which in-turn lead to both poor neurologic and prognostic outcomes.

Conclusion

Both endovascular and NS groups had comparable major strokes and complications, though there were higher grades and incremental MFS score and greater difference in MFS score in NS aneurysm clipping group than endovascular aneurysm coiling group. Although minor complications were comparable in both the groups; prolonged morbidity and hospital stay were observed in NS group owing to craniotomy in comparison to coil embolization group (uneventful intraoperative group cases). To conclude, we recommend prospective studies incorporating the functional clinical outcomes scale: Modified Rankin's Scale (MRS)27 along with the Modified Fisher's Scale (MFS)28 for further comparative study in both groups in terms of clinical and prognostic outcomes for management of ruptured aneurysmal SAH.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Non-traumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage.Intensive Care Medicine. New York, NY: Springer; 2007.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Warning signs and symptoms of subarachnoid hemorrhage. South Med J. 2009;102(01):21-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worst headache and subarachnoid hemorrhage: prospective, modern computed tomography and spinal fluid analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32(03):297-304. Pt 1

- [Google Scholar]

- Meta-analysis of computed tomography angiography versus magnetic resonance angiography for intracranial aneurysm. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(20):e10771.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intracranial aneurysms in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: CT angiography as a primary examination tool for diagnosis—systematic review and meta-analysis. [published correction appears in Radiology 2011;260(2):612] Radiology. 2011;258(01):134-145.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43(06):1711-1737.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: looking to the past to register the future. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(06):1157-1166. discussion 1166–1167

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk of shunt-dependent hydrocephalus after occlusion of ruptured intracranial aneurysms by surgical clipping or endovascular coiling: a single-institution series and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(05):924-933. discussion 933–934

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multidisciplinary management and emerging therapeutic strategies in aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(05):504-519.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of a neuro-intensivist on patients with stroke admitted to a neurosciences intensive care unit. Neurocrit Care. 2008;9(03):293-299.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the emerging revolution. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3(05):256-263.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intracranial aneurysms: recent advances in management.Frontiers in Biomedicine. Boston, MA: Springer; 2000.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Intracranial aneurysms: a review of endovascular and surgical treatment in 248 patients. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 1998;41(02):81-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage is independent of the type of aneurysm therapy. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(06):1244-1250. discussion 1250–1251

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combined management of intra-cranial aneurysms by surgical and endovascular treatment. Modalities and results from a series of 395 cases—comments. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1999;141:562.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupture during coiling of intracranial aneurysms: predictors and clinical outcome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;165:81-87.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Collaborative Group. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neuro-surgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9342):1267-1274.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage causing cardiopulmonary arrest: resuscitation profiles and outcomes. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2011;51(09):619-623.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Active bleeding from ruptured cerebral aneurysms during diagnostic angiography: emergency treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(10):2062-2065.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes after aneurysm rupture during endovascular coil embolization. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(05):1059-1066. discussion 1066–1067

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coil embolization versus clipping for ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a meta-analysis of prospective controlled published studies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(09):1764-1768.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARITY Investigators. Ruptured intracranial aneurysms: factors affecting the rate and outcome of endovascular treatment complications in a series of 782 patients (CLARITY study) Radiology. 2010;256(03):916-923.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher revised scale for assessment of prognosis in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69(06):910-913.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of symptomatic vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the modified fisher scale. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(01):21-27. discussion 21–27

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of 3 radiographic scales for the prediction of delayed ischemia and prognosis following subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(02):199-207.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of cerebral infarction and patient outcome in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: comparison of new and established radiographic, clinical and combined scores. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(01):111-119.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retrospective review analysisof interventional radiologic endovascular-coil embolizationversus neurosurgical clipping in management of intracranialaneurysms. Int J Recent Surgical Med Sci 2018

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]