Translate this page into:

Prognostic Factors Associated with Mortality in Cirrhotic Patients with Bleeding Varices

Address for correspondence Mohammed Elsayed Elhendawy, MD, Department of Tropical Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, El-Giash Street, Tanta 31527, Egypt (mohamed.elhendawy@med.tanta.edu.eg).

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective

Bleeding gastroesophageal varices are a cause of high mortality among cirrhotic patients. The aim of this study was to study prognostic factors for mortality in cirrhosis associated with variceal bleeding.

Patients and Methods

This prospective study was conducted on 100 cirrhotic patients admitted to the Tanta University Hospital with an acute first variceal bleeding episode. Baseline clinical, laboratory, and endoscopic findings were recorded at presentation.

Results

During the first 6 weeks 15 patients died, 3 following the initial bleed and 12 after an early rebleed. At 6 months, a further 21 patients had died. Statistical analysis utilizing the baseline data revealed that high early death rate was associated with number of blood units transfused, lower systolic blood pressure, thrombocytopenia, increased serum creatinine and international normalized ratio (INR). High MELD, AIMS56, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II (APACHE II) and ROCKall scores were risk factors for mortality. Risk factors for early rebleeding included presence of diabetes mellitus, leucocytosis, high Child score, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), AIMS56, and sepsis-associated organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores. A high Child score, presence of ascites, and associations such as hepatic encephalopathy and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, leucocytosis, elevated alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, bilirubin, INR, and creatinine as well as low albumin were associated with decreased survival.

Conclusion

High MELD, AIMS56, APACHE II, and ROCKall scores were risk factors for mortality after acute variceal bleeding. High death rate during the first 6 weeks is associated with anemia, hypotension, thrombocytopenia, increased serum creatinine, and INR. Decreased survival at 6 months is associated with increased Child score, presence of ascites and associations such as hepatic encephalopathy and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Keywords

liver cirrhosis

variceal bleeding

mortality

encephalopathy

Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is the loss of blood through the GI tract originating proximal to the Treitz angle.1 Acute hemorrhage from varices is one of most menacing portal hypertension complications and related to high morbidity and mortality.2 The prognosis of cirrhotic patients is related to severity of the hepatic condition liver which could be assessed using the Child–Turcotte–Pugh (CTP) classification, with higher scores having a significant impact on survival times.3

Portal hypertension leads to the development of portosystemic collateral venous vessels. Every year 5 to 10% of patients with cirrhosis will develop esophageal varices.4 This is more likely to occur in patients with progressive cirrhosis and may be present in up to 60% of patients with decompensated cirrhosis.5

Mortality rates following a first variceal bleed in cirrhotics increase with advancement of the Child score and range between 15 and 80%.6 The main causes of death are unstoppable hemorrhage, infection and kidney failure. There are multiple determinants linked to increased mortality and poor prognosis including high MELD scores, kidney failure, hepatic venous pressure gradients above 20 mm Hg, and evidence of an active bleed on endoscopy.7,8

It is uncertain if the currently used prognostic scores, namely the CPT and MELD scores are reliable in determination of acute variceal hemorrhage risk.

The aim of the current study was to identify the prediction model most suitable for determining the outcome of acute variceal bleeding.

Patients and Methods

This study was a prospective study performed on 310 patients with upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding, 210 were excluded and 100 were included from October 2017 to December 2018. They were collected from Tropical Medicine Department and Internal Medicine Department, Tanta University Hospital.

Inclusion criteria:

Cirrhotic patients with bleeding varices (esophageal, fundal, or both).

Exclusion criteria:

Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Patients with upper GI hemorrhage due to causes other than ruptured varices (peptic ulcers and erosions, esophagitis, malignant masses, and vascular ectasia).

The study was approved by the ethical review board, Tanta University, Faculty of Medicine, with approval code 31779/09/2017. All patients participating in the study provided a signed informed consent. The study protocol abides by the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki 1975 guidelines and was approved by the faculty's human research committee.

A meticulous history was taken from all patients and they were subjected to thorough examination and monitoring. All relevant laboratory tests were performed including baseline and serial liver function tests and serum creatinine. Blood counts, electrolyte, and arterial blood gas levels, as well as amounts of blood transfused were recorded. An upper GI endoscopy was done to diagnose the cause of bleeding and enable making appropriate treatment decisions. All the patients underwent abdominal ultrasonography.

The recorded baseline data were used to calculate various prognostic scores including CTP, MELD, APACHE II (acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II), AIMS65, sepsis-associated organ failure assessment (SOFA) and the ROCKall scores.

The primary end point: survival and rebleeding within 6 weeks after the first variceal bleeding attack.

The secondary end point: survival for 6 months after the first variceal bleeding attack.

Statistical Analysis

Mean, standard deviation, Student's t-test, and chi-square test were performed by Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS StatisticsVersion 20) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

Results

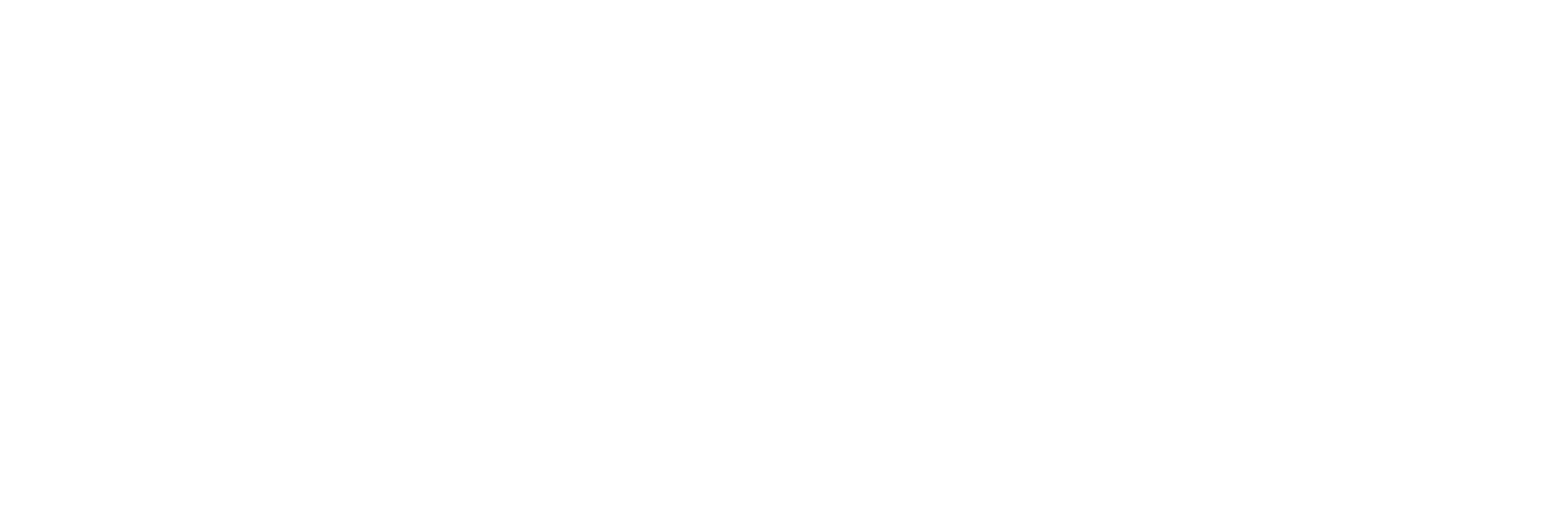

This study was a prospective study performed on 310 patients with upper GIT bleeding presented to Tanta University Hospital: 210 patients had been excluded (either refused or not met the inclusion criteria) and 100 patients had been included from October 2017 to December 2018. After the first attack of bleeding 85 patients lived and 15 patients died; after 6 months 64 patients were survivors and 21 did not survive. Total deaths after 6 months were 36 patients (►Fig. 1).

- Study analysis population.

Risk Factors for Death After the First Attack of Bleeding

After the first attack of bleeding 15 patients died out of total 100 patients enrolled in the study. Regarding age, sex, smoking, presence of ascites, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension there were no statistically significant differences between the patients.

There were significant differences between the studied patients as regards the number of blood units (p < 0.001). More the blood units needed, worse the prognosis. There were no significant differences between the studied patients as regards Sungestaken tube inflation before the endoscopy, associations (hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome), proton pump infusion before endoscopy, and beta blockers intake (►Table 1).

| Outcome after first bleeding attack | Chi-square | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsurvivor | Survivor | Total | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 | p-Value | ||

| Complaint | Hematemesis | 7 | 46.67 | 34 | 40.00 | 41 | 41.00 | 1.194 | 0.550 |

| Melena | 3 | 20.00 | 29 | 34.12 | 32 | 32.00 | |||

| Both | 5 | 33.33 | 22 | 25.88 | 27 | 27.00 | |||

| Number of blood units | No | 7 | 46.67 | 22 | 25.88 | 29 | 29.00 | 11.291 | 0.046a |

| One | 0 | 0.00 | 30 | 35.29 | 30 | 30.00 | |||

| Two | 6 | 40.00 | 14 | 16.47 | 20 | 20.00 | |||

| Three | 1 | 6.67 | 9 | 10.59 | 10 | 10.00 | |||

| Four | 1 | 6.67 | 9 | 10.59 | 10 | 10.00 | |||

| Five | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.18 | 1 | 1.00 | |||

| Sungestaken tube usage | No | 14 | 93.33 | 84 | 98.82 | 98 | 98.00 | 1.961 | 0.161 |

| Yes | 1 | 6.67 | 1 | 1.18 | 2 | 2.00 | |||

| Association (SBP, HRS, HE) | No | 5 | 33.33 | 35 | 41.18 | 40 | 40.00 | 0.327 | 0.568 |

| Yes | 10 | 66.67 | 50 | 58.82 | 60 | 60.00 | |||

| Proton pump infusion | No | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 3.53 | 3 | 3.00 | 0.546 | 0.460 |

| Yes | 15 | 100.00 | 82 | 96.47 | 97 | 97.00 | |||

| Beta blockers | No | 13 | 86.67 | 67 | 78.82 | 80 | 80.00 | 0.490 | 0.484 |

| Yes | 2 | 13.33 | 18 | 21.18 | 20 | 20.00 | |||

Abbreviations: HE, hepatic encephalopathy; HRS, hepatorenal syndrome; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

aStatistically significant.

There was no significant difference between the studied patients as regards the endoscopic findings, variceal grades, and method of intervention.

There was significant difference between the studied patients as regards systolic blood pressure–the lower the systolic blood pressure, the worse the prognosis. Also thrombocytopenia, increased serum creatinine, and INR are risk factors for increased death rate (►Table 2).

| Outcome after first bleeding attack | t-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsurvivors (mean ± SD) | Survivors (mean ± SD) | T | p-Value | |

| Hemoglobin | 8.413 ± 1.215 | 8.482 ± 1.031 | 0.233 | 0.817 |

| WBCs | 6.160 ± 4.577 | 6.206 ± 3.904 | 0.041 | 0.967 |

| Platelets | 135.000 ± 55.554 | 104.188 ± 49.957 | 2.166 | 0.033a |

| ALT | 31.400 ± 11.306 | 35.800 ± 36.419 | 0.462 | 0.645 |

| AST | 52.533 ± 17.067 | 56.812 ± 28.533 | 0.562 | 0.576 |

| Bilirubin | 3.467 ± 4.667 | 2.339 ± 2.558 | 1.364 | 0.176 |

| Albumin | 2.733 ± 0.623 | 2.965 ± 0.474 | 1.660 | 0.100 |

| INR | 1.593 ± 0.616 | 1.339 ± 0.396 | 2.090 | 0.039a |

| Creatinine | 1.313 ± 0.558 | 1.037 ± 0.352 | 2.546 | 0.012a |

| Urea | 57.333 ± 27.105 | 45.882 ± 32.298 | 1.294 | 0.199 |

| Child Score | 8.867 ± 3.067 | 8.000 ± 2.345 | 1.257 | 0.212 |

| MELD score | 17.600 ± 7.935 | 12.682 ± 5.583 | 2.938 | 0.004a |

| AIMS56 | 2.133 ± 1.552 | 1.071 ± 0.961 | 3.561 | 0.001a |

| APACHE II | 7.267 ± 6.147 | 4.459 ± 3.194 | 2.666 | 0.009a |

| SOFA score | 3.467 ± 1.767 | 3.376 ± 1.739 | 0.185 | 0.854 |

| ROCKall | 4.667 ± 1.839 | 3.212 ± 1.544 | 3.269 | 0.001a |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; INR, international normalized ratio.

aStatistically significant.

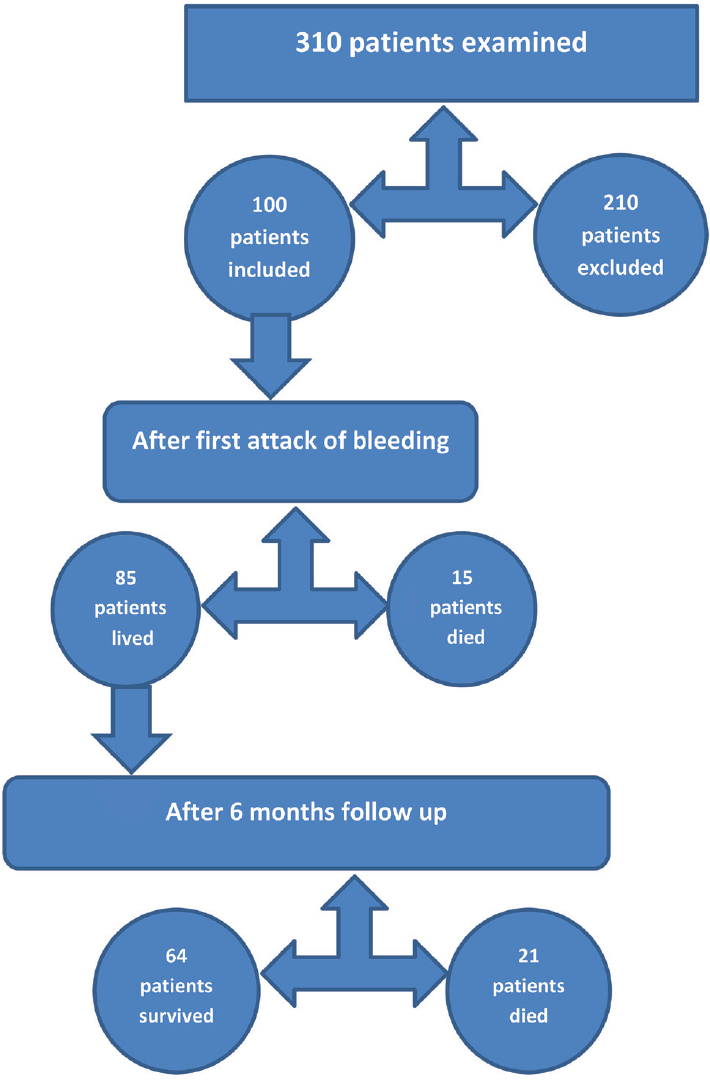

Significant differences were noted between the studied patients as regards the MELD score, AIMS56 score, APACHE II score, and ROCKall score (p ≤ 0.001). Increased MELD, AIMS56, APACHE II, and ROCKall scores were risk factors for mortality. Child score wasn't associated with mortality (►Table 2; ►Fig. 2).

- Receiver operating characteristic curve for scores for outcome after first bleeding attack.

AIMS56 score has 92.94 sensitivity, 26.67 specificity, and 57.7% accuracy.

ROCKall score has 80.00 sensitivity, 73.33 specificity, and 74.4% accuracy. ROCKall score was the most suitable score for predicting mortality after the first attack of bleeding.

Risk Factor of Early Rebleeding Within 6 Weeks After the First Bleeding Attack

Presence of diabetes mellitus was associated with increased risk of rebleeding (►Table 3).

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 58.182 ± 8.125 | 56.667 ± 6.746 | 0.617 | 0.539 |

| SBP | 108.750 ± 10.701 | 99.167 ± 7.930 | 2.987 | 0.004a |

| DBP | 66.932 ± 9.512 | 59.167 ± 7.930 | 2.699 | 0.008a |

| Hemoglobin | 8.478 ± 1.084 | 8.425 ± 0.841 | 0.164 | 0.870 |

| Hemoglobin after first | 9.485 ± 0.798 | 9.717 ± 0.610 | −0.965 | 0.337 |

| WBCs | 5.872 ± 3.553 | 8.600 ± 6.002 | −2.270 | 0.025a |

| Platelets | 109.727 ± 53.109 | 102.083 ± 41.507 | 0.478 | 0.634 |

| ALT | 31.375 ± 12.530 | 62.750 ± 90.148 | −3.144 | 0.002a |

| AST | 53.375 ± 18.906 | 76.667 ± 57.105 | −2.895 | 0.005a |

| Total bilirubin | 2.084 ± 1.437 | 5.617 ± 7.131 | −4.180 | <0.001a |

| Direct bilirubin | 1.114 ± 0.869 | 3.300 ± 4.375 | −4.232 | <0.001a |

| Serum albumin | 2.981 ± 0.485 | 2.558 ± 0.487 | 2.829 | 0.006a |

| INR | 1.336 ± 0.392 | 1.678 ± 0.654 | −2.582 | 0.011a |

| Prothrombin activity | 74.244 ± 18.631 | 62.000 ± 23.909 | 2.062 | 0.042a |

| Serum creatinine | 1.044 ± 0.372 | 1.331 ± 0.508 | −2.396 | 0.018a |

| Urea | 43.886 ± 26.052 | 74.833 ± 52.587 | −3.328 | 0.001a |

| Child Score | 7.898 ± 2.344 | 9.833 ± 2.791 | −2.623 | 0.010a |

| MELD score | 12.841 ± 5.669 | 17.667 ± 8.348 | −2.601 | 0.011a |

| AIMS56 score | 1.136 ± 1.095 | 1.917 ± 1.165 | −2.298 | 0.024a |

| APACHE II score | 4.682 ± 3.564 | 6.333 ± 5.662 | −1.392 | 0.167 |

| SOFA score | 3.193 ± 1.589 | 4.833 ± 2.125 | −3.215 | 0.002a |

| ROCKall score | 3.409 ± 1.679 | 3.583 ± 1.621 | −0.339 | 0.736 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; INR, international normalized ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

aStatistically significant.

The studied patients differed significantly regarding their systolic blood pressure, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), WBCs, total bilirubin, serum albumin, INR, and prothrombin activity, serum creatinine and urea, leucocytosis, increased ALT, AST, bilirubin, INR, activity, and serum creatinine.

Significant differences were recorded as regards Child score, MELD score, AIMS56 score, and Sofa score. Increases Child, MELD, AIMS56, and Sofa scores were risk factors for early rebleeding. No such differences were recorded as regards APACHE II score and ROCKall score.

Factors Affecting Outcome 6 Months After Bleeding

The studied patients were matched as regards age or sex (►Table 4). Presence of ascites was associated with decreased survival.

| Outcome after 6 months | t-test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died | Alive | T | p-Value | ||

| Hemoglobin | Range | 6.4–11.5 | 6.1–10.5 | 1.067 | 0.289 |

| Mean ± SD | 8.690 ± 1.147 | 8.414 ± 0.990 | |||

| WBCs | Range | 2.5–23.9 | 2.3–24.8 | 2.108 | 0.038a |

| Mean ± SD | 7.733 ± 5.217 | 5.705 ± 3.263 | |||

| Platelets | Range | 40–150 | 40–430 | −1.569 | 0.121 |

| Mean ± SD | 89.476 ± 33.957 | 109.016 ± 53.533 | |||

| ALT | Range | 17–343 | 10–62 | 2.393 | 0.019a |

| Mean ± SD | 51.857 ± 68.623 | 30.531 ± 12.623 | |||

| AST | Range | 26–245 | 12–133 | 2.956 | 0.004a |

| Mean ± SD | 72.095 ± 44.050 | 51.797 ± 19.134 | |||

| Total bilirubin | Range | 0.9–21 | 0.6–8.8 | 3.434 | 0.001a |

| Mean ± SD | 3.905 ± 4.246 | 1.825 ± 1.385 | |||

| Direct bilirubin | Range | 0.2–15.1 | 0.2–5 | 3.117 | 0.003a |

| Mean ± SD | 2.319 ± 3.156 | 0.988 ± 0.801 | |||

| Serum albumin | Range | 2–3.4 | 2–4.1 | −4.966 | <0.001a |

| Mean ± SD | 2.571 ± 0.345 | 3.094 ± 0.439 | |||

| INR | Range | 1.03–3.4 | 1–2.2 | 3.511 | 0.001a |

| Mean ± SD | 1.586 ± 0.611 | 1.258 ± 0.252 | |||

| Prothrombin activity | Range | 24–95 | 34–100 | −2.636 | 0.010a |

| Mean ± SD | 65.214 ± 24.094 | 77.438 ± 16.238 | |||

| Serum creatinine | Range | 0.6–2.6 | 0.6–2 | 2.991 | 0.004a |

| Mean ± SD | 1.227 ± 0.458 | 0.974 ± 0.287 | |||

| Urea | Range | 24–220 | 20–154 | 3.130 | 0.002a |

| Mean ± SD | 64.095 ± 50.075 | 39.906 ± 21.165 | |||

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; INR, international normalized ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

aStatistically significant.

Associations as hepatic encephalopathy and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis were associated with decrease survival.

There were significant differences between the studied patients as regards WBCs, ALT, AST, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, serum albumin, INR, prothrombin activity, serum creatinine, and urea. Leucocytosis, increased ALT, AST, bilirubin, INR, activity, serum creatinine, and urea decrease albumin associated with decrease survival.

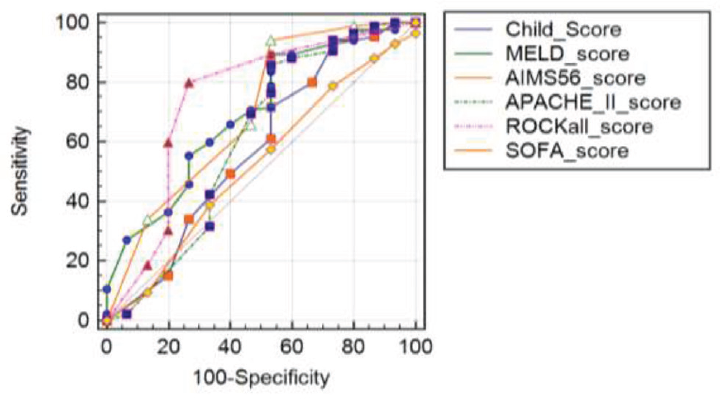

Child scores were significantly different between studied patient groups on the contrary to the MELD score (►Fig. 3).

- Receiver operating characteristic curve between MELD and Child scores for 6 months survival.

ROC curve shows that Child score had 65.62 sensitivity, 95.24 specificity, and 88.7% accuracy, whereas MELD score had 100.00 sensitivity, 21.43 specificity, and 55.5% accuracy.

Discussion

Variceal hemorrhage is a complication of cirrhosis that denotes decompensation and that still has a high mortality rate.9

Even though management of variceal hemorrhage has improved in the last decades, 6-week mortality following a GI bleed remains high at around 10 to 20%, and rises with advanced cirrhosis.10

In this study, there was significant difference between the studied patients as regard blood pressure. Our findings agree with those of Gado et al,11 and Jiménez et al.12 They found that hemodynamic instability at admission, Child class C, blood in GI tract at the index endoscopy, rebleeding within five days of endoscopy, and in-hospital complications were independent predictors of mortality.

We have detected significant differences between the studied patients as regards associations (hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, thrombocytopenia, increase serum creatinine, raised INR, and prolonged prothrombin time), as did Goldis et al.13

No significant differences were recorded as regards proton pump inhibitor (PPI) infusion. This finding was in disagreement with Komori et al,14 who found an association between regular PPI treatment before and after the onset of variceal bleeds and increments in short as well as long-term mortalities. This could be explained by the increased risk of infections such as bacterial infections in general and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis following regular PPI use.15,16

We detected significant difference between the studied patients as regards MELD score, ROCKall score, and AIMS65 score. This finding was in agreement with Saltzman et al,17 and Gado et al.11 This finding was in disagreement with Mohammad et al,18 who reported the superiority of the SOFA score in mortality prediction when compared with the MELD, APACHEII, and CPT scores and concluded that independently the AIMS65 score was the simplest and most applicable scoring system for mortality prediction among cirrhosis patients suffering from acute variceal hemorrhage.

Early Rebleeding Risk Factors

We had 12 patients presented with early rebleeding; we found that leucocytosis, increased ALT, AST, bilirubin, INR, prothrombin activity, and serum creatinine and decreased albumin associated with increased risk of rebleeding. This finding was in agreement with Jiménez et al,12 who found that low systolic blood pressure, high creatinine, and albumin levels were independent factors associated with rebleeding. In our study increased Child, MELD, AIMS56, and Sofa scores were risk factors for early rebleeding, as was stated by Goldis et al.13

Follow-up of Studied Patients after 6 Months

Higher numbers of blood/blood product units transfused in the current study were significantly associated with increased mortality, as noted by the research of both Al-Freah et al,19 and Triantos et al.20 However Gado et al,11 did not record such a finding in their study.

The present study records an association between leukocytosis, increased liver transaminases and total bilirubin as well as decreased serum albumin with a higher risk of mortality. This is consistent with the findings of Cannon et al,21 and Moledina et al.22 They found that elevated leucocyte counts, serum ALT, serum total bilirubin, and a lack of endoscopy were independent mortality predictors.

There was significant difference in the prothrombin activity and the international normalized ratio (INR) in nonsurvivors, as also reported by Bishay et al.

Increased serum creatinine and urea in non survivors was significantly associated with mortality. This finding is congruent with that of Jiménez et al,12 whose study including 507 patients with GI bleeding, found that high creatinine levels were independent risk factors for rebleeding of variceal and nonvariceal upper GI bleeding.

In this study, Child–Pugh score was more predictive of mortality than MELD score after 6 months. This finding was in disagreement with Hassanien et al,23 who found that MELD scores were more predictive of mortality than the Child–Pugh scores in HCC patients with bleeding varices, it may be explained by poor hepatic reserve as indicated by Child class C and higher MELD score, advanced tumor stage of patients, higher portal venous pressure, presence of more complications of liver cirrhosis, and associated major comorbidity.

Conclusion

High MELD, AIMS56, APACHE II, and ROCKall scores were risk factors for mortality after acute variceal bleeding. High death rate during the first 6 weeks is associated with anemia, hypotension, thrombocytopenia, increased serum creatinine, and INR. Decreased survival at 6 months is associated with increased Child score, presence of ascites, and associations such as hepatic encephalopathy and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Recommendations

We recommend use of prognostic scores, in particular the Rockall score for prediction of mortality after a first attack of variceal bleeding.

Patients with high serum creatinine, low serum albumin, and high Child scores should be monitored carefully following variceal hemorrhage as they have lower survival rates.

We suggest adding points to the MELD score for patients with advanced liver disease and those on liver transplantation waiting list when they experience a variceal bleed.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Clinical practice. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to a peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2367-2376.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improved survival after variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis over the past two decades. Hepatology. 2004;40(03):652-659.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long term survival and severe rebleeding after variceal sclerotherapy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;171(06):489-492.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology and demographics of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: prevalence, incidence, and mortality. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2011;21(04):567-581.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic Therapy for Esophageal Variceal Hemorrhage.Current Surgical Therapy. (12th ed). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. p. :339.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of variceal bleeding: solving the puzzle. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85(10):1426-1427.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of early re-bleeding and mortality after acute variceal haemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Gut. 2008;57(06):814-820.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improved survival of cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding over the decade 2000-2010. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39(01):59-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child-Turcotte-Pugh class is best at stratifying risk in variceal hemorrhage: analysis of a US multicenter prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(05):446-453.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63(03):743-752.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of mortality in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage who underwent endoscopy and confirmed to have variceal hemorrhage. Alexandria Journal of Medicine. 2015;51:295-304.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhospital and delayed mortality after upper gastrointestinal bleeding: an analysis of risk factors in a prospective series. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(06):714-720.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features, endoscopic management and outcome of patients with non-variceal upper digestive bleeding by Dieulafoy lesion. Biol Med (Aligarh). 2017;9:4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic factors associated with mortality in patients with gastric fundal variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(03):496-504.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proton pump inhibitor use significantly increases the risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in 1965 patients with cirrhosis and ascites: a propensity score matched cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(06):695-704.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proton pump inhibitor treatment is associated with the severity of liver disease and increased mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(05):459-466.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(06):1215-1224.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients: what is the best prognostic score? Turk J Gastroenterol. 2016;27(05):464-469.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of scoring systems and outcome of patients admitted to a liver intensive care unit of a tertiary referral centre with severe variceal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(11):1286-1300.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predicting failure to control bleeding and mortality in acute variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 2008;48(02):185-188.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of white blood cell count with increased mortality in acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina pectoris. OPUS-TIMI 16 Investigators. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(05):636-639.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for mortality among patients admitted with upper gastrointestinal bleeding at a tertiary hospital: aprospective cohort study Moledina and Komba BMC. Gastroenterology. 2017;17:165.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical factors associated with mortality in cirrhotic patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2019:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and acute variceal bleeding. Electron Physician. 2015;7(06):1336-1343.

- [Google Scholar]