Translate this page into:

Occurrence of Adrenal Suppression in Patients Having Sepsis in Indian Population and Impact of Corticosteroid Supplementation on Its Overall Survival

Address for correspondence Sidharth Sraban Routray, MD, Department of Anaesthesiology and Critical Care, S.C.B. Medical College and Hospital, Cuttack, Odisha 753007, India (e-mail: drsidharth74@gmail.com).

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective

Our aim was to estimate the occurrence of adrenal suppression in critically ill patients with septic shock who have got admission in intensive care unit and to evaluate the effectiveness of hydrocortisone in these patients in relation to mortality of patient, development of septic shock, and effect on total leucocyte count.

Methods

Serum cortisol was measured in 120 patients with sepsis. Patients with decreased cortisol level were split in to two groups (group A and B). Group A received 50 mg of hydrocortisone 6 hourly and group B was given matching placebo. At day 7, serum cortisol level was estimated for both A and B groups. The results were calculated and compared with relation to incidence of adrenal insufficiency, development of septic shock, effect on total leucocyte count, and survival at 28 days.

Results

The occurrence of adrenal suppression in patients having sepsis in our study was 44 out of 120 patients, that is, 36.6%. After supplementation of corticosteroid for 7 days the mean value of serum cortisol of group A was 40.38 ± 8.44 µg/dL and group B was 24.30 ± 6.47 µg/dL (p < 0.001). At day 7, in group A, 22.7% developed septic shock, whereas in group B, 36.4% developed septic shock (p < 0.001). In group A and B, mortality rate of the patients at 28 days was 18.2 and 22.7%, respectively.

Conclusion

Hydrocortisone supplementation in critically ill patients with low random basal serum cortisol level with sepsis does not significantly improve the overall survival.

Keywords

adrenal suppression

sepsis

Indian population

corticosteroid

Introduction

Sepsis is a systemic life-threatening illness, which is marked by inflammation and abnormal defense response to infection in host. The clinical profile of patients varies from mild symptoms to very severe symptoms and signs. Septic shock and multiorgan dysfunction are usual complications.1 In the developed world, occurrence of septic shock was 8.2% of all intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, in which the death rate was 55 to 62.1%.2 Sepsis is currently the most significant cause of mortality in all ICUs worldwide. Mortality rate is as high as 30 to 50% in spite of advanced treatment.3 So, there is need for further investigations and early goal-directed treatment. The debate about supplementation of steroids in management of septic shock was started in 1915 when suprarenal apoplexy was diagnosed.4 Cahalane and Waters in their study found hemorrhage in adrenal gland in a patient of meningococcal septicemia. They concluded that adrenal hemorrhage resulted in acute adrenal suppression leading to death.5 Many authors have studied the role of steroid supplementation in the management of septic shock but study outcomes were controversial.6,7 Annane8 and Briegel et al9 first studied the role of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in septic shock. They found higher rates of adrenal suppression in these patients in whom glucocorticoid supplementation increased the longevity. There was very few data in literature regarding the occurrence of adrenal suppression in Indian population having septic shock.10 The primary aim of this research was to evaluate the incidence of adrenal suppression in patients with sepsis, as measured by random serum cortisol levels. The secondary objectives were to evaluate the impact of such dysfunction, and eventually to predict the usefulness of serum cortisol testing and the effectiveness of hydrocortisone in these patients in relation to mortality of patient, development of septic shock, and effect on total leucocyte count (TLC).

Methods

Our trial is a randomized and prospective trial conducted after approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee from August 2018 to November 2020 at central ICU, S.C.B. Medical College and Hospital, Odisha, India. All the patients have given written and informed consent.

Study Setting

This study was conducted in the central ICU of the S.C.B. Medical College and Hospital.

Study Design

This is a prospective randomized study.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients with evidence of sepsis.

Patients of both sexes.

Age group of 18 to 65 years.

Serum albumin > 2.5 g/dL.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients < 18 years and > 65 years.

Patients with a known disease involving the HPA axis.

Patients already on some form of glucocorticoid treatment.

Patients with multiorgan dysfunction syndrome.

Patients with established septic shock on inotropic support.

Serum albumin < 2.5 g/dL.

American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Definitions11

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) requirements:

Temperature more than38.3°C or less than 36°C.

Pulse rate more than 90 beats per minute.

Breathing rate more than 20/minute or PaCO2 < 32 mm Hg (< 4.3 kPa).

Leucocyte count more than 12,000 cells/mm3 or < 4000 cells/mm3 or > 10% immature forms (band).

Any two of the above criteria must be satisfied to be labeled as to have SIRS. Evidence of sepsis was pronounced as patients satisfying minimum two criteria of the SIRS with evidence of infection like either positive bacterial cultures or elevated procalcitonin (PCT) > 2 ng/mL. PCT levels < 0.5 ng/mL is taken as normal. PCT concentrations between 0.5 and 2 ng/mL indicate the chance of sepsis. PCT level between 2 and 10 ng/mL strongly indicate sepsis. Severe sepsis is sepsis associated with organ damage, including, but not limited to, acute oliguria, arterial hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 < 300), coagulation abnormalities (international normalized ratio >1.5 or activated partial thromboplastin time > 60 seconds), and altered sensorium. Septic shock is confirmed when sepsis is present with persistent hypotension, instead of requisite fluid therapy, together with signs of abnormal perfusion (hyperlactatemia > 1 mmol/L and decreased capillary refill or mottling). Serum cortisol levels were measured for all patients satisfying the inclusion criteria, at the time of inclusion in the study at day 1. Blood pressure, respiratory rate, and temperature of all the patients included in the study were recorded at day 1. Those patients having decreased serum cortisol level were randomly divided into two groups–group A and group B. Group A received 50 mg of hydrocortisone 6 hourly and group B was given matching placebo. At day 7, serum cortisol level was estimated for both group A and B. The results were calculated and compared in relation to development of septic shock, effect on total white blood cell count, and survival at 28 days/death.

Serum Cortisol Testing

Immunoassay method was used to measure cortisol level. This was total serum cortisol which included both free cortisol and the cortisol bound to cortisol binding globulin (CBG) and albumin. This value is dependent on the serum albumin levels, a surrogate for CBG. Hence only patients with a serum albumin > 2.5 g/dL were enrolled in this trial. A total cortisol value of < 20 µg/dL was considered subnormal. There is no demonstrable circadian rhythm in serum cortisol levels in seriously ill patients due to altered HPA axis. So the samples for serum cortisol testing were drawn randomly at any time of the day. All the observed data was tabulated and statistically analyzed and compared among the two groups.

Statistical Software

Data analysis was done using statistical software SPSS 22.0. Continuous measurements data was presented as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical measurement data was presented as number (%). Randomization among the study participants was done using computer-generated random number in 1:1 sequence. Student's t-test was used for continuous data. Homogeneity of variance was tested by Leven's test. Fisher's exact test was used for categorical data. A p-value of < 0.001 was taken as highly significant.

Results

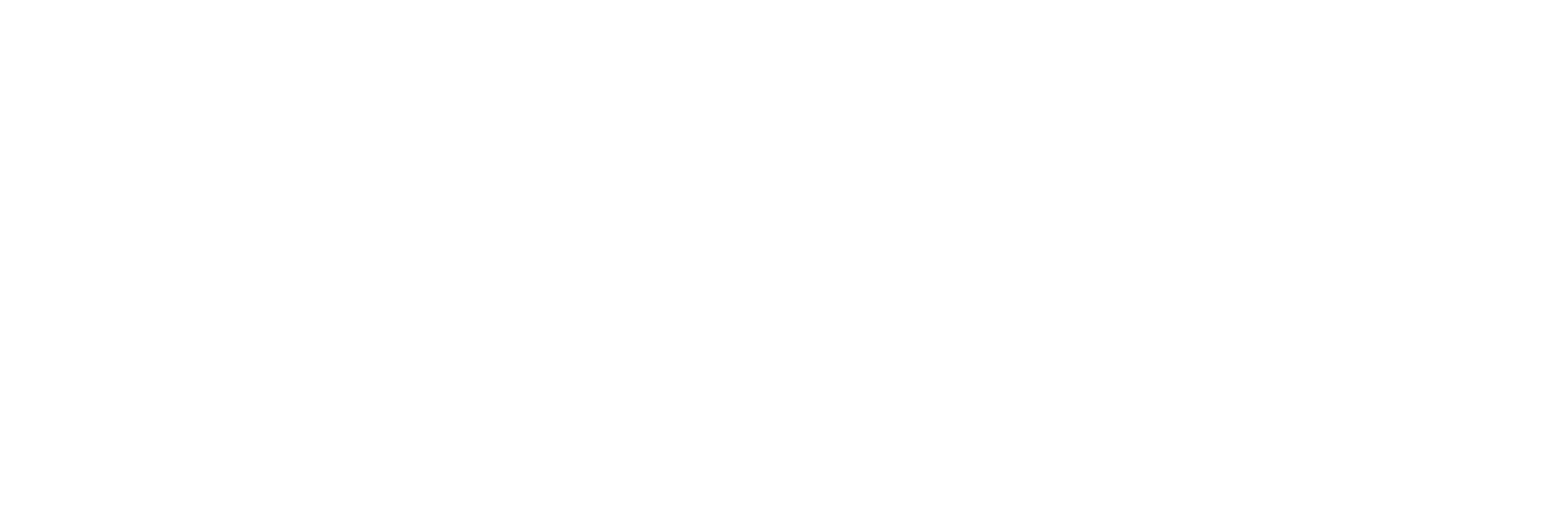

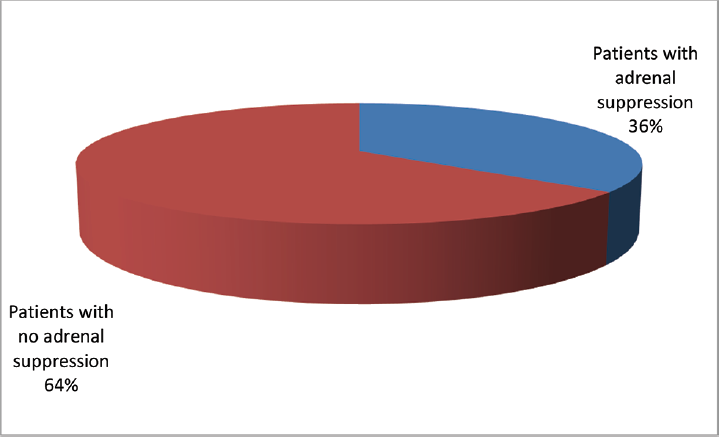

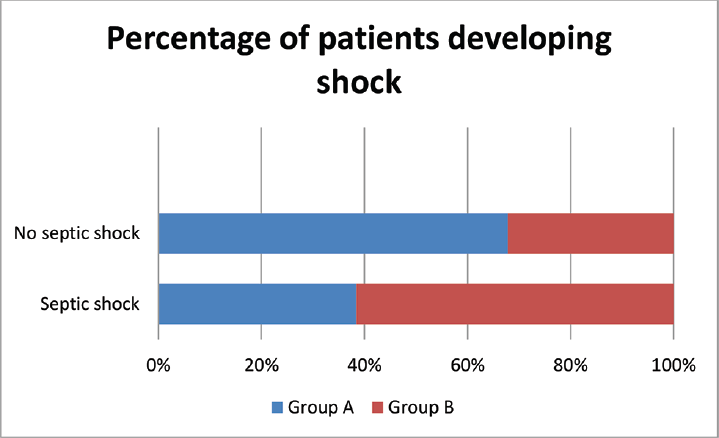

A total of 120 symptomatic patients of either sex, aged 18 to 65 years who were found positive for sepsis were included in this study. Random serum cortisol level was estimated in all these patients at the day of admission. Out of these 120 patients adrenal insufficiency is found in 44 patients (males 26 and females 18). These 44 patients were randomized into two groups: group A and group B. Group A received 50 mg of hydrocortisone 6 hourly and group B was given matching placebo. At day 7, serum cortisol level was estimated for both group A and group B. The incidence of development of septic shock, effect on TLC, and survival at 28 days/death was recorded. In both the groups, empirical broad spectrum antibiotics were started soon after recruitment in the study after sending the samples for bacterial culture and sensitivity. The occurrence of adrenal suppression in patients with sepsis in our study was 44 out of 120 patients, that is, 36.6% (►Fig. 1). There was no notable variation between the two groups with regard to pulse rate, breath rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and temperature on day 1(►Table 1). The mean value of serum cortisol at day 1 in group A was 10.36 ± 2.69 µg/dL and in group B was 10.73 ± 2.93 µg/dL with p-value = 0.670. So, both these groups were comparable with respect to serum cortisol level at day 1. After exogenous supplementation of corticosteroid for 7 days the mean value of serum cortisol of group A was 40.38 ± 8.44 µg/dL and group B was 24.30 ± 6.47 µg/dL (p < 0.001) (►Table 2). At day 1, mean TLC of group A was 14,336 ± 2593.87/mm3 and that of group B was 14,350 ± 2351/mm3 with p-value = 0.986. So both these groups were comparable with respect to TLC at day 1. After 7 days of corticosteroid therapy mean TLC value of group A was 12136.24 ± 2611.84/mm3 and that of group B was 13645.45 ± 4482.95/mm3. Though there is some decrease in TLC in group A in contrary to group B but it was not significant (►Fig. 2). At day 7 in group A, 5 out of 22 patients, that is, 22.7%, there was development of septic shock. Whereas in group B, 8 out of 22 patients, that is, 36.4%, went into septic shock. There was no notable variation seen among group A and group B with respect to development of septic shock at day 7 (►Fig. 3). Mortality rate of the patients at day 28 in group A was 18.2% (4 out of 22) and in group B was 22.7% (5 out of 22) which was statistically not significant (►Fig. 4).

- Occurrence of adrenal suppression.

- Total leucocyte count (TLC) in two groups.

- Development of septic shock in patients in the two groups at day 7.

- Overall survival of patients studied in two groups at day 28.

| Variables | Group A (mean ± SD) | Group B (mean ± SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | 110.09 ± 8.25 | 108.55 ± 7.74 | 0.525 |

| Respiratory rate (min) | 18.41 ± 2.36 | 17.77 ± 2.00 | 0.340 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 105.55 ± 9.42 | 105.09 ± 9.58 | 0.643 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 68.27 ± 5.10 | 67.91 ± 4.60 | 0.805 |

| Temperature (°F) | 102.10 ± 1.74 | 102.38 ± 1.23 | 0.539 |

Abbreviations: bpm, beats per minute; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

| Serum cortisol (µg/dL) | Group A (mean ± SD) | Group B (mean ± SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| At day 1 | 10.36 ± 2.69 | 10.73 ± 2.93 | 0.670 |

| At day 7 | 40.38 ± 8.44 | 24.30 ± 6.47 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

The occurrence of adrenal suppression in seriously ill patients was varied greatly in different studies. Suresh et al12 in their study concluded that the incidence of adrenal suppression in septic shock was 42% and has also found that basal serum cortisol level was higher in Indian population as compared with western data which is in agreement with our study. Shenker and Skatrud13 have found 59% occurrence of adrenal suppression in patients with sepsis and cited that the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency presents significant challenges in the critical care setting. The pathophysiological mechanism is currently discussed critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency.14 Wu et al15concluded that most of the critically ill patients had reduced serum cortisol levels. Reduced cortisol levels may indicate worse prognosis. They advocated for repeated testing function of adrenal gland in critically ill patients. Mani16quoted that relative adrenal insufficiency in septic shock existed in Indian patients and that there was a basis to use reduced dose of corticosteroids. Annane et al17 in their study opined that treatment with hydrocortisone resulted improvement in patient survival which contradicts our study. However, Bernard18 concluded that convincing proof that corticosteroids are useful pharmacologic agents in the treatment of severe sepsis remained elusive which was similar to our study. Prigent et al19 in their study concluded that glucocorticoids supplementation could revamp the outcome in critically ill patients. Surviving Sepsis Campaign20 did not recommend routine use of reduced dose of hydrocortisone in septic shock, which is similar to our study. In a study by Sprung et al,21 the members of the Corticosteroid Therapy of Septic Shock (CORTICUS) trial, concluded that hydrocortisone neither improved the survival of critically ill patients nor produced any improvement in shock, which is similar to our study. In a study by Venkatesh et al22 (ADRENAL study), they concluded that the use of hydrocortisone did not resulted in any improvement in death rate at 90 days. But there was notable betterment in morbidity of critically ill patients. Those patients treated with hydrocortisone had a reduced vasopressor requirement and lesser days of mechanical ventilation which resulted in shorter ICU stay. But there was no difference in parameters like mortality after 28 days, return of shock, and requirement of dialysis. Keh et al23 tested hydrocortisone therapy in critically ill patients having severe sepsis and concluded that hydrocortisone did not produce any improvement in septic shock. Yildiz et al24 concluded that hydrocortisone supplementation reduced the mortality rates of the patients who were critically ill but it was not significant. The above studies were in agreement with our study. In contrast to our study, Rady et al25 concluded that corticosteroids supplementation increased mortality and morbidity in critically ill patients as it increased the susceptibility to nosocomial infections, and exacerbated critical illness neuropathy and myopathy. So each critically ill patient must be evaluated carefully for corticosteroids supplementation.

Conclusion

We concluded that occurrence of adrenal suppression in seriously ill patients with sepsis in our set up is 36.67%. The rise in serum cortisol level after corticosteroid supplementation has no role in prevention of septic shock. Hydrocortisone supplementation in critically ill patients having low random basal serum cortisol level with sepsis does not significantly improve the overall survival.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(08):801-810.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of sepsis: an update. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(07):S109-S116.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(07):1303-1310.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulminant meningococcal septicaemia. A hospital experience. Lancet. 1975;2(7925):120-121.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steroid controversy in sepsis and septic shock: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 1995;23(07):1294-1303.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corticosteroid treatment for sepsis: a critical appraisal and meta-analysis of the literature. Crit Care Med. 1995;23(08):1430-1439.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meta-analysis: the effect of steroids on survival and shock during sepsis depends on the dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(01):47-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortisol replacement for severe sepsis and septic shock: what should I do? Crit Care. 2002;6(03):190-191.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of the adrenocortical response during septic shock and after complete recovery. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(09):894-899.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reversal of late septic shock with supraphysiologic doses of hydrocortisone. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(04):645-650.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(02):580-637.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serum cortisol level in Indian patients with severe sepsis/septic shock. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2017;10(04):194-198.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrenal insufficiency in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(07):1520-1523.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI) in critically ill patients (Part I): Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) 2017. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1751-1763.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrenal insufficiency in prolonged critical illness. Crit Care. 2008;12(03):R65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Return of corticosteroids for septic shock - new dose, new insights. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2004;8(03):145-147.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288(07):862-871.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International Sepsis Forum's controversies in sepsis: corticosteroids should not be routinely used to treat septic shock. Crit Care. 2002;6(05):384-386.

- [Google Scholar]

- Science review: mechanisms of impaired adrenal function in sepsis and molecular actions of glucocorticoids. Crit Care. 2004;8(04):243-252.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(03):486-552.

- [Google Scholar]

- CORTICUS Study Group. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(02):111-124.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ADRENAL Trial Investigators and the Australian-New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group. Adjunctive glucocorticoid therapy in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(09):797-808.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of hydrocortisone on development of shock among patients with severe sepsis: the HYPRESS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(17):1775-1785.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physiological-dose steroid therapy in sepsis [ISRCTN36253388] Crit Care. 2002;6(03):251-259.

- [Google Scholar]

- Corticosteroids influence the mortality and morbidity of acute critical illness. Crit Care. 2006;10(04):R101.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]