Translate this page into:

Asymptomatic implant removal after fracture union based on request to remove. Is it worth considering, an Indian perspective?

*Corresponding author: Prof. Sanjay Rai, Department of Orthopaedics, Military Hospital Ambala Cantt, Ambala, Haryana, India. skrai47@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Gupta T, Bawaskar AA, Kamboj P, Gurav PP, Rai S. Asymptomatic implant removal after fracture union based on request to remove. Is it worth considering, an Indian perspective? Int J Recent Surg Med Sci. 2023;9:111-6. doi 10.25259/IJRSMS-2023-3-15.

Abstract

Objectives

Hardware removals are among the commonly performed surgical procedures in orthopedics, but they sometimes prove quite difficult. The purpose of our study was to evaluate the risk, benefit and drawbacks of asymptomatic implant removal based on patients’ desire.

Material and Methods

A total of 105 patients who had been previously treated for a fracture and voluntarily wanted its removal and who did not report clinical indications or occasional regional pain were included in the study cohort.

Results

For the 105 patients surveyed, implant removals were performed in the leg (41 patients; 39%), the ankle joint (32 patients; 30%), the thigh (19 patients; 18%) and the forearm and the wrist (15 patients; 14%). The most common indication for removal was patients’ request in 66 (62.8%) cases. Altogether, 98 (93%) patients were satisfied because of the fulfillment of their desire, despite the instances of complication being frequent (32.8%).

Conclusion

In our study, we reported a surprisingly high rate of satisfied patients after surgical hardware removal once their requests for hardware removal were taken into consideration. However, it was closely associated with multiple risks. Therefore, judicious selection of actually eligible patients is highly recommended instead of the unqualified fulfilment of their requests for removal.

Keywords

asymptomatic implant

implant removal

patient desire

patient safety

INTRODUCTION

The surgical removal of orthopedic hardware or implants used for the fracture fixation of bones is considered as one of the most commonly performed orthopedic surgeries.[1] In a study conducted in Germany in 2010, a total of 1,80,000 hardware removals were performed, making this type of surgery the fourth-most common surgical procedure in the orthopedic field.[2]

However, there is still a debate in the literature regarding the justification of elective surgical implant removal.[3,4] The common indications for removal are surgical site infection, loosening of implant, metal allergy, implant failure, soft tissue compromise and union failure; the minor indications include intended improvement of function, regional pain, foreign body sensation, implant irritation and MRI compatible issues. However, the above mentioned literature does not offer any instances of implant removal based on patients’ desire because “implants are simply not required once fracture has fully united”.

In a 2008 study by Hanson, which included 730 patients in Davos, Switzerland, 380 of 655 surgeons (58%) disagreed that routine implant removal was unnecessary while 48% felt that removal was riskier than leaving an implant in situ. These findings were probably influenced by various unwanted complications that could occur during and after implant removal.[5–9] The socioeconomic impact of implant removal must therefore also be taken into consideration, especially in a developing country like India, where less only than 20% of the total population has access to medical insurance. In fact, hardware removal is cost- and time-consuming for both patients and hospitals, and any complication would further increase the financial burden on patients, leading to emotional breakdown and feelings of disheartenment.

Our study aimed to evaluate the risk, benefit and drawbacks of asymptomatic implant removal based solely on patients’ request, using a simple, easily comprehensible and self-explanatory questionnaire. We hypothesized that our patients’ satisfaction after implant removal would be high when their requests for removal had been taken into consideration since patients tend to avoid keeping a metal throughout life if doing so is not required, despite the possibility of associated post-surgery complications.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Our study was conducted in two hospitals by the same team of surgeons between February 2018 and August 2022. Overall, 105 consecutive patients aged between 10 and 65 years (mean age of 37 years) were included in the study. Patients with occasional pain at the site of implant, especially in winter due to unknown reasons, were also included. In summary, this study included 39 women, 56 men and 10 children (aged between 10 and 15 years). All of the patients’ fractures were united radiographically and were deemed clinically asymptomatic. Notably, the study was conducted only after the approval of a relevant institutional review board, and all patients signed an informed consent form agreeing to participate in the same.

First, all patients were carefully examined to rule out any clinical indications for removal. Accordingly, patients who had previously undergone hardware removal for a known cause – such as infection, implant irritation, implant failure, painful implant and fracture non-union – were excluded from the study. The study aimed to evaluate the patients’ satisfaction levels after asymptomatic implant removal on patients’ request, that is, the request for implant removal by asymptomatic patients.

At 6 months after removal, a patient satisfaction questionnaire was prepared for all the patients of our cohort. It consisted of two questions: (1) Are you happy and satisfied that the hardware was removed and (2) What are your overall experiences after surgery?

Moreover, the Short Musculoskeletal Function Assessment Questionnaire (SMFA) and the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Short Form-36 (SF-36), two standardized surveys assessing functional outcomes, were recorded as a baseline at 3, 6 and 12 months after removal (to obtain post-operative data). In addition, SF-36 health survey score questionnaires were used both preoperatively and post-operatively, and as per the scores recorded, many patients were deemed satisfied and asymptomatic. Furthermore, information was obtained from each patient (interview, pain score, SF-36, SMFA) from their respective hospital chart (injury and treatment information) and their post-operative radiographs (healing of the fracture, type of plate and screws, and prominence of the hardware) for our study. To determine each patient’s satisfaction level, she or he was interviewed by one of the authors.

Inclusion criteria

-

Age between 10 and 65 years

-

Previous surgical fixation with metallic implant

-

Fracture union had occurred

-

Patients who were asymptomatic but requested implant removal

-

No previous attempt had been made to remove the implant

Exclusion criteria

-

Fracture was not yet fully united

-

Failed attempt at implant removal in the past

-

Symptomatic implant, for example, infection, implant irritation, implant failure, fracture non-union, loosening and migration of implant

RESULTS

For the 105 patients surveyed, implant removals were performed in the leg (41 patients; 39%), ankle joint (32 patients; 30%), thigh (19 patients; 18%) and forearm and the wrist (15 patients; 14%). Out of the total number of patients, 10 were children in the 10- to 15-year age group. Among them, six had fractured shaft femur and were treated by plating, while the remaining four were treated for fractured radius and ulna. The hardware of all 10 children (9% of the entire cohort) were removed within 1 year since index surgery, as desired by their parents. Notably, the most common indication for hardware removal was patients’ request (66 patients; 62.8%), while surgeon recommendation – in cases of previous surgery– was the indication for 23 patients (21.9%). Moreover, MRI compatibility issues served as the indication for 5 patients (4%), while 11 patients (10.4%) thought that their pain occurred due to their implant.

The demographic characteristics of the entire study population are shown in Table 1. Out of the entire cohort, 98 (93%) patients were satisfied irrespective of the nature of the specific implant removed. All of the 10 children (9.5%) in the cohort underwent removal operations within one year since their index surgery [Table 2]. In addition, the types of implants and the different anatomical sites are shown in Table 3. Interestingly, we noted various peri- and post-operative complications in 35 (32.8%) patients.

| Age of patients | No. of patient – n (%) |

| 10–15 | 10 (9.5%) |

| 16–25 | 25 (23.8%) |

| 26–35 | 11 (10.4%) |

| 36–45 | 33 (31.4%) |

| 46–55 | 14 (13.3%) |

| 56–65 | 12 (11.4%) |

| Male | 49 (46.6%) |

| Female | 56 (53.3%) |

| Upper limb | 13 (12.3%) |

| Lower limb | 92 (87.6%) |

| Mechanism of injury | |

| Road accident | 42 (40%) |

| Sports related | 29 (27.6%) |

| Fall from height | 12 (11.4%) |

| Hit while walking on road | 13 (12.3%) |

| Assault | 9 (8.5%) |

| Type of fracture | |

| Closed | 69 (65.7%) |

| Open | |

| Grade I | 25 (23.8%) |

| Grade II | 7 (6.6%) |

| Grade IIIA | 2 (1.9%) |

| Grade IIIB | 2 (1.9%) |

| Time of removal after the initial operation | No. of patients |

| <6 months | 04 (3.8 %) – all 04 children |

| 7–12 months | 06 (5.7%) – all 06 children |

| 13–18 months | 11 (10.4%) |

| 19–24 months | 29 (27.6%) |

| 24–36 months | 47 (44.7%) |

| >36 months | 7 (6%) |

| Implant | Femur | Tibia | Malleolus | Radius | Ulna | Clavicle | Humerus |

| Total Nails | 12 (11.4%) | 10 (9.5%) | |||||

| Solid nails | 2 | ||||||

| Cannulated | 10 | 3 | |||||

| Material | - | ||||||

| Titanium | 3 | 10 | |||||

| Steel nail | 9 | ||||||

| Total Plates | 6 (5%) | 11 (10.4%) | 19 (18%) | 9 (8%) | 12 (11.4%) | 14 (13.3%) | |

| DCP | 2 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 9 | 11 | |

| LCDCP | 4 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Material | |||||||

| Titanium | 2 | 2 | 7 | - | 3 | 5 | |

| Steel | 4 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| Screws | 12 (11.4%) |

DCP: Dynamic compression plate, LCDCP: Low contact dynamic compression plate

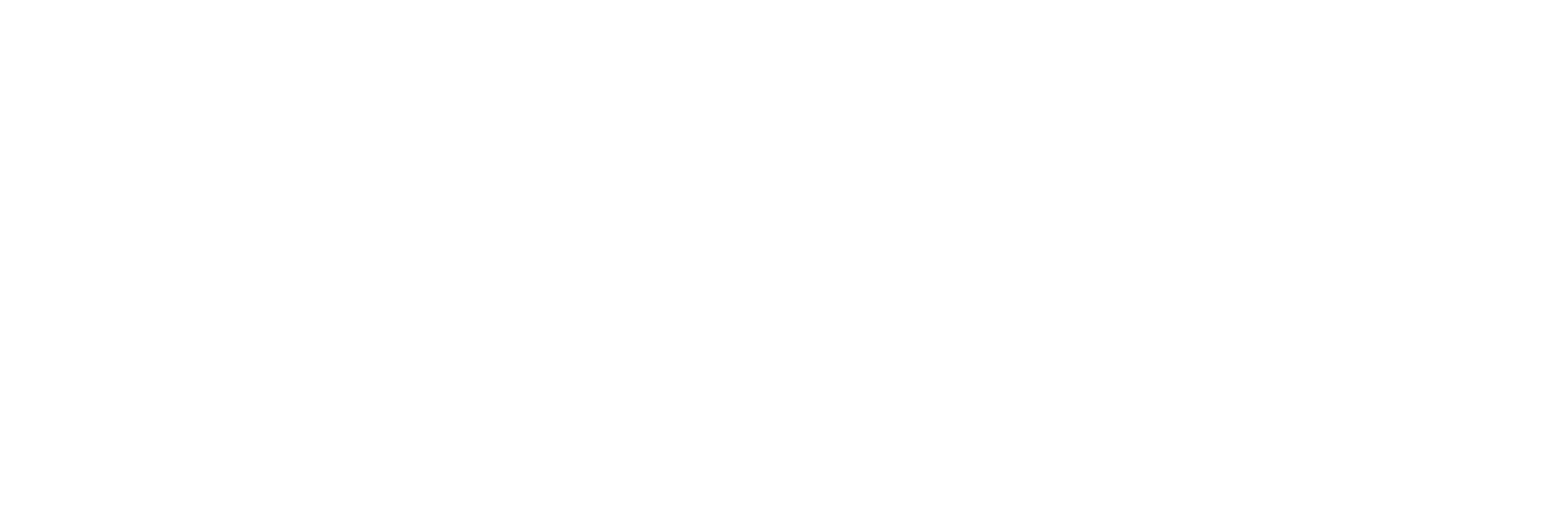

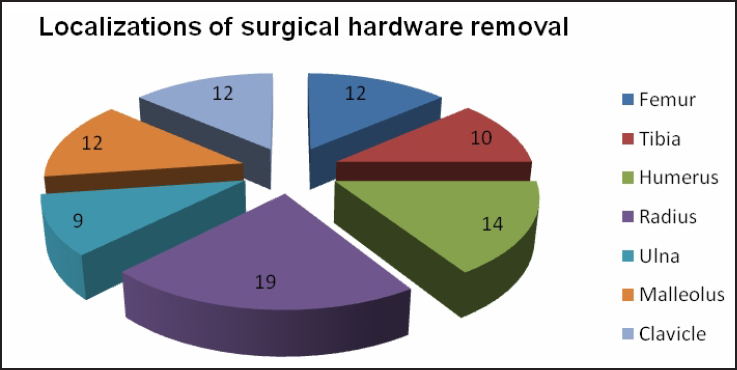

Furthermore, the localisations of surgical hardware removal from body parts are shown in Figure 1. As per Figure 2, delayed wound healing was the most common complication in 31% of the cohort, followed by infections. To reiterate, patients’ request was the most common reason for surgical removal of implant [Figure 3].

- Localisations of surgical hardware removal.

- Post-operative complications following removal of asymptomatic orthopedic implants.

- Indications of implant removal.

As mentioned above, the most common indication for hardware removal in our study was patients’ desire – in 66 (62.8%) cases – while surgeon recommendation (in cases of previous surgery) was the indication in 23 (21.9%) cases. MRI compatibility issues served as the indication in five (04%) cases, while 11 patients (10.4%) thought that their occasional pain was due to their implants.

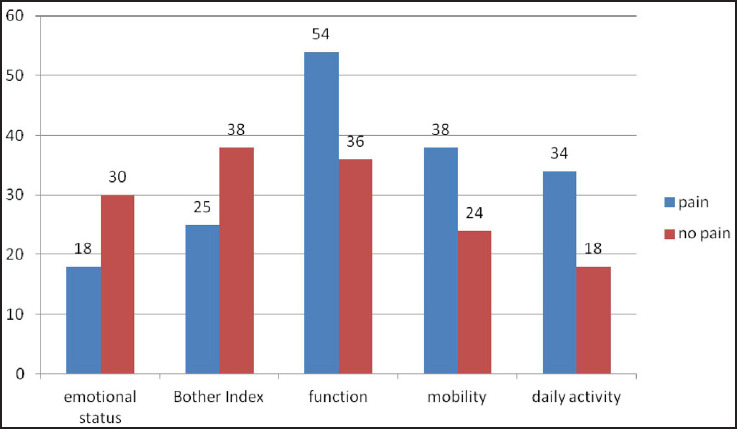

Of the cohort, 69% exhibited high satisfaction levels upon the fulfilment of their desire, reporting significant subjective improvements in overall function after implant removal. In this vein, the scores of the SF-36 are shown in Figure 4, with higher scores indicating higher functional levels. Notably, the mean SF-36 scores for patients with implant-related pain (n = 11) were significantly lower in all the sub-score areas. The greatest of such difference was observed regarding pain where a given implant was located; in this regard, patients who thought that their hardware induced pain had a mean score of 42.6 ± 31.4, whereas pain-free patients who still desired hardware removal had a mean score of 71.3 ± 28.5 (p = 0.0006). The average scores regarding emotional status were 31.82 ± 19.20 for patients with pain and 26.76 ± 16.3 for patients without pain (p = 0.001). Table 4 contains the SMFA scores for the dysfunction and bother indices at pre-surgery (baseline) and after implant removal.

- Selected SMFA sub-scores for patients with and without a hardware-related problem. Lower the scores better the function. Statistical significance was reached for each sub-score presented (p < 0.006 for all).

| Variable | n | Pre-surgery | Post-surgery | ||

| Dysfunction mean bother mean (SD) | Dysfunction mean bother mean (SD) | ||||

| Upper limb with implant | 13 | 37.5 (21) | 30.7 (13) | 31.5 (21) | 21.6 (11) |

| Lower limb with implant | 92 | 39.2 (22) | 33.8 (14) | 25.6 (13) | 22.2 (11) |

| Child with implant | 10 | 35.7 (19) | 42.7 (31) | 22.6 (13) | 23.7 (12) |

DISCUSSION

In our study, the patients had a positive experience insofar as their requests for orthopedic implant removal were considered. Of the total cohort who underwent orthopedic implant removal, 65% reported high satisfaction levels, despite minor complications being reported, for example, impaired wound healing occurring during or after the procedure. The patients clearly articulated that they were happy and satisfied, especially because many surgeons had previously refused to consider their request for implant removal in the absence of clinical indications.

Patient experiences and function after implant removal

Our study data revealed a high percentage of patient satisfaction and the subjective improvement of function after implant removal. Indeed, 98 (93%) patients out of the total cohort were satisfied with their implant removal. This finding speaks to many previous studies that have reported variable improvements in pain after implant removal. For example, Brown et al., in their study of ankle plate removal, have shown a 50% concomitant improvement in pain.[10] Gustilo[11] has also reported an improvement in knee pain, from 64% to 96%, after removal of the nail.

In our study, the desired satisfaction levels were achieved as 93% of the cohort desired to remove their implants. This finding aligns with those of many related studies that have shown that the removal of implants improves function.[12,13]

Patient satisfaction after orthopedic implant removal

Surprisingly, 93% of our cohort, and additionally 65% of those patients who subjectively perceived some complications regarding wound healing (although minor) after hardware removal, reported that they would opt for implant removal again, if required. This finding adds to the gap in the literature regarding the relations between implant removal and patients’ desire and their satisfaction after removal. Indeed, our study indicates that patient satisfaction can be surprisingly high even with complications subsequent to implant removal, if the reason for hardware removal is their own personal request.

Crucially, in our study, the patients were seemingly more satisfied after foreign material was removed from their own body, even with the potential disadvantages such as post-operative complications being associated with this kind of surgery. This was a refreshing finding in the locational context of India, where many orthopedic surgeons remain very reluctant to remove asymptomatic implants only based on patient requests, leading to emotional torment and adverse psychological impacts on patients’ health.

However, metallosis is an alarming complication that may arise where the quality of implant is not always reliable, especially within a developing country. Ideally, clinically asymptomatic implants should not be removed because of the risk of complications. This view has been supported by Gosling et al., who have noted increases in pain in 20% of asymptomatic individuals (under study) after nail removal from femur; Gosling et al. have concluded that only patients suffering from pain after femoral nailing would improve after or benefit from implant removal.[14] Unno et al. have also shown that implant removal should not be considered a routine procedure and should be decidedly undertaken after detailed clinical examination.[15] Plus, Sidky et al., in their study of 130 patients, have revealed a tibial intramedullary (IM) nail removal rate of 23.9%, additionally reporting an improvement in 72.2% of their patients’ symptoms after nail removal.[16] Williams et al.,[17] in a prospective study of 69 patients, have recorded notable pain relief upon the removal of painful implants. Kovar et al.[18] who performed 424 hardware removals in 371 consecutive patients following a proximal femur fracture, and divided their patients into two groups – with the clinically indicated group consisting of 299 patients (80.59%) and with 72 patients (19.41%) being grouped as the non-clinically indicated group – have noted that non-clinically indicated implant removal should be avoided due to the higher complication rates (as high as 28%). Again, Onche et al., in their study cohort of 47 patients, have recorded patient requests as the main indication for removal in 34 patients (72.3%), symptomatic implants as the indication for four patients (8.5%), surgeon’s request without any symptoms as the indication for seven patients (14.9%) and six patients (10.7%) were symptomatic, where four (8.5%) due to postoperative chronic osteomyelitis and two patients (4.3%) in intractable pain. Onche et al. have concluded that plates should be removed from the lower limb because of the stress-shielding effect of the plates. Furthermore, IM nails are stress-sharing devices and can be left in situ.[19] Jamil et al. have claimed that generally metallic implants should be removed once their purpose is served.[20] Even Mølster et al., in their questionnaire-based study, have concluded that although implant removal is desirable after fracture healing, it is also associated with a certain morbidity and with the incidence of complications.[21]

A related study by Reith et al. has asserted that implants should be removed by default, being associated with post-operative complications at a rate of 10%.[22] In contrast, a study by Raney et al., within the pediatric age group, has not found any conclusive evidence in the literature to support or refute the practice of routine implant removal in children.[23]

LIMITATIONS

This study focused on patient experience and satisfaction with respect to a particular surgical intervention based on their desires. Data collection was also limited to verbal focus-group interviews with a small cohort of patients. Thus, it inherently offers limited transferability. Therefore, future research should investigate patients’ experiences in a variety of contributory roles across different surgical fields in order to draw stronger conclusions. Clearly, the establishment of definite correlations between psychological factors, patient satisfaction and clinical improvement warrants further investigations.

CONCLUSION

In our study, we noted a high rate of satisfied patients after surgical hardware removal despite the explained and noticed complications. Hence, we suggest that implants should only be removed in light of clinical indications and not merely be based on patient requests. Although the concomitant complication risk is considered to be only as high as 32.8%, keeping in mind patients’ safety and quality of life, any indication for asymptomatic implant removal still has to be assessed and scrutinized judiciously.

In summary, patient requests cannot be considered as the absolute indication for implant removal. Nevertheless, the removal of implant gives patients a high level of satisfaction. In our study, the majority of patients considered the futility of keeping a metal in their bodies throughout their lives even when it was not required, despite the surgeon’s opinion that it would not be necessary to remove their implants even after the fracture union.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to all our patients who participated in the study and departmental staff without whose help this study would not have been completed.

Ethical approval

The research/study complied with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964.

Declaration of patients consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

REFERENCES

- Routine implant removal after fracture surgery: a potentially reducible consumer of hospital resources in trauma units. J Trauma. 1996;41:846-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refracture of long bones after implant removal. An avoidable complication? Der Unfallchirurg. 2012;115:323-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardware removal: indications and expectations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:113-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metal removal after osteosyntheses. Indications and risks. Der Orthopade. 2003;32:1039-57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surgeons’ beliefs and perceptions about removal of orthopaedic implants. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Observations on removal of metal implants. Injury. 1992;23:25-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardware removal after pelvic ring injury. Der Unfallchirurg. 2012;115:330-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indication, timing and complications of plate removal after forearm fractures: results of a metaanalyses including 635 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86-B(SUPP III):289.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of hardware-related pain and its effect on functional outcomes after open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:271-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knee pain after intramedullary tibial nailing: its incidence, etiology, and outcome. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11:103-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Functional outcomes after syndesmotic screw fixation and removal. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:12-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Functional outcomes following syndesmotic fixation: a comparison of screws retained in situ versus routine removal–is it really necessary? Injury. 2013;44:1880-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Femoral nail removal should be restricted in asymptomatic patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;423:222-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardware removal after tibial fracture has healed. Can J Surg. 2008;51:263.

- [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The benefits of implant removal from the foot and ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:1316-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Complications des ablations de matériel après fracture synthésée du col fémoral: une étude observationnelle sur seize ans. Revue de chirurgie orthopédique et traumatologique. 2015;101:521.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Removal of orthopaedic implants: indications, outcome and economic implications. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2011;1:101.

- [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Do orthopaedic surgeons need a policy on the removal of metalwork? A descriptive national survey of practicing surgeons in the United Kingdom. Injury. 2008;39:362-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hip fracture implants increase serum metal levels. Scandinavian journal of clinical and laboratory investigation. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2006;66:705-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metal implant removal: benefits and drawbacks–a patient survey. BMC Surg. 2015;15:96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-based analysis of removal of orthopaedic implants in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:701-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]